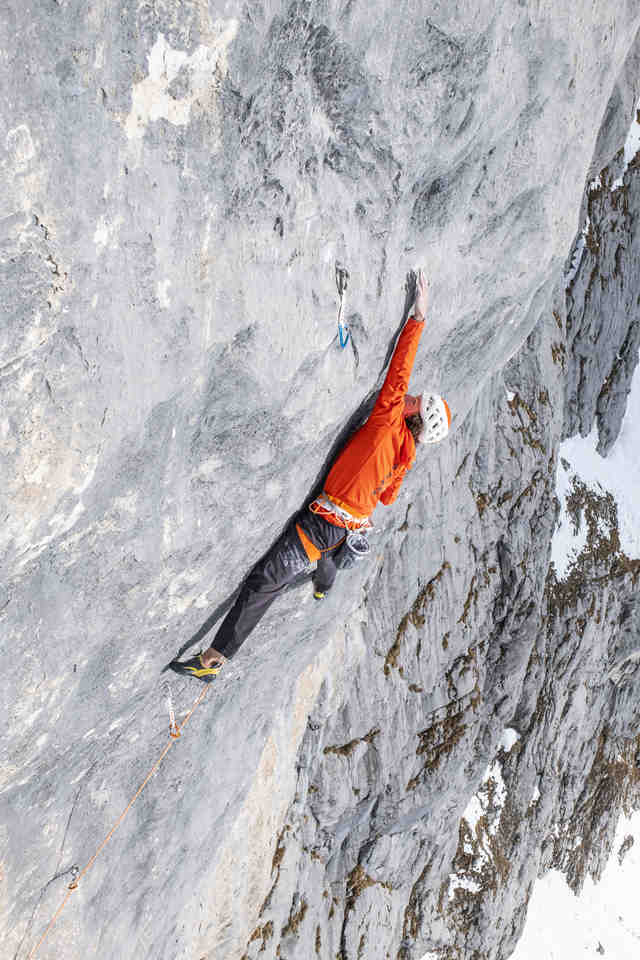

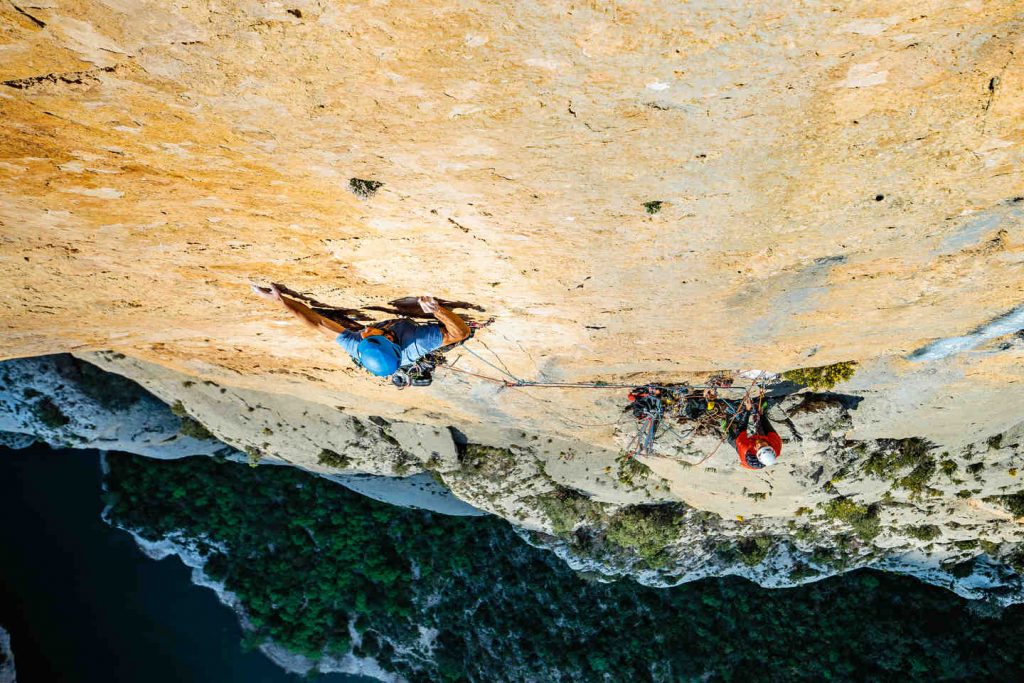

A quite place in Sweden ideal for trad climbing using Totem Cams

Bohuslän remains one of Europe’s quiet climbing corners — under the radar and unhurried. Unlike the crowded granite hotspots of the Alps, here the days unfold gently, with no pressure, no agenda, just easy decisions, solid rock, and a pace of life that invites you to slow down and enjoy it. The local community is genuinely welcoming of climbers, adding to the sense that this is a place where you’re not just passing through, but part of something quietly special.

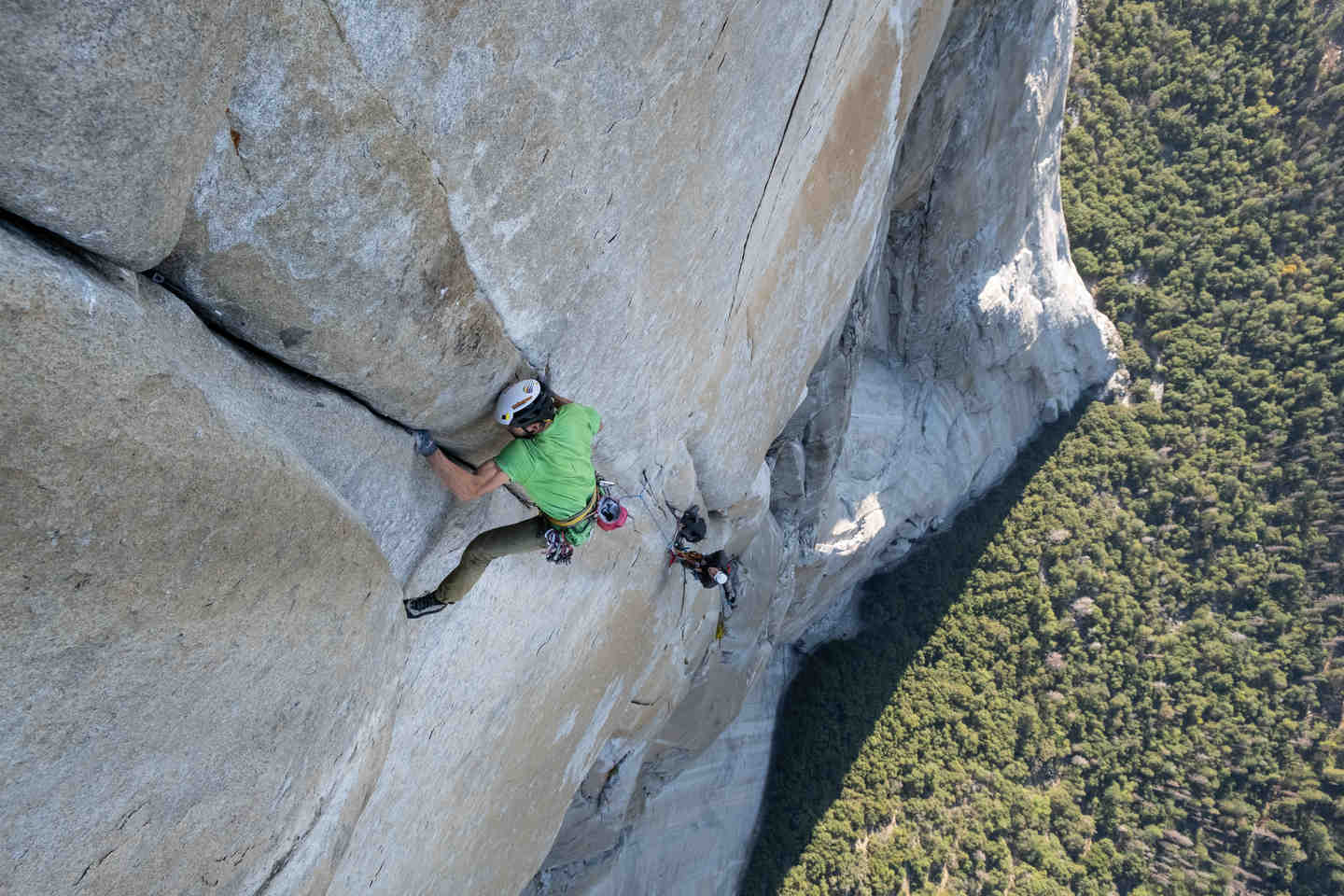

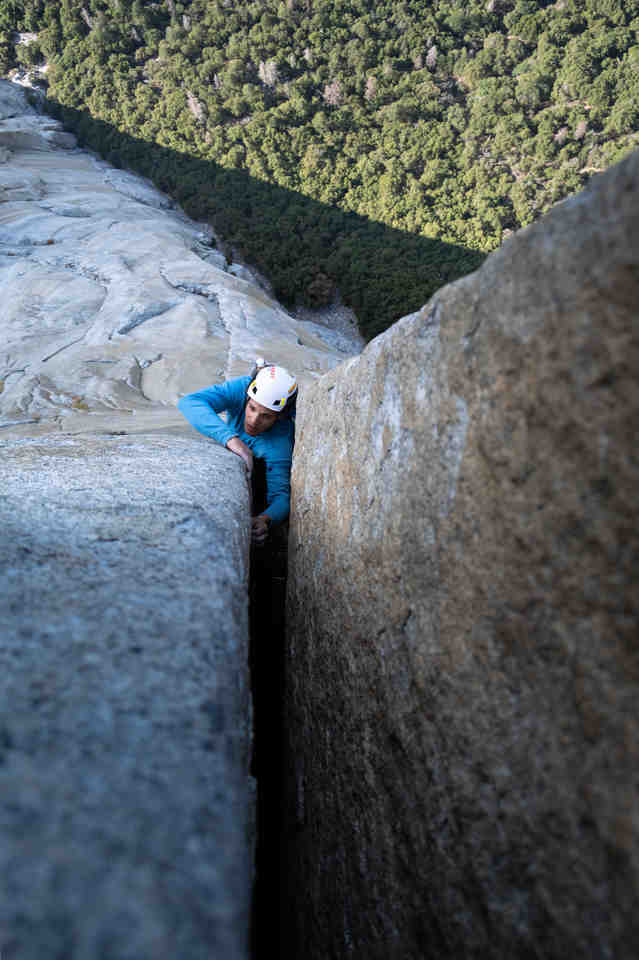

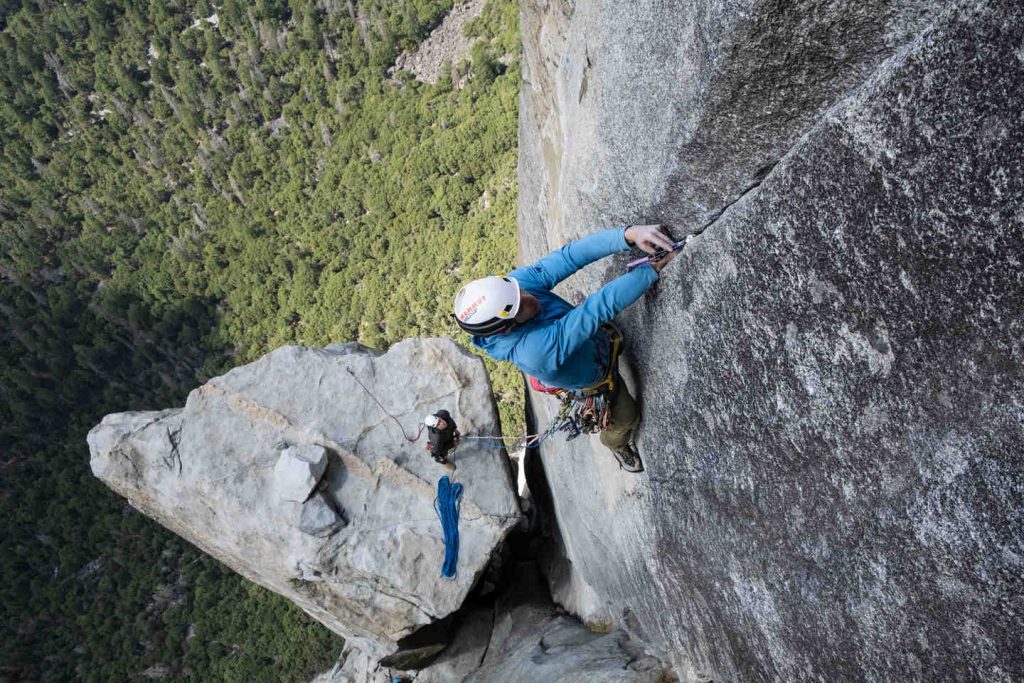

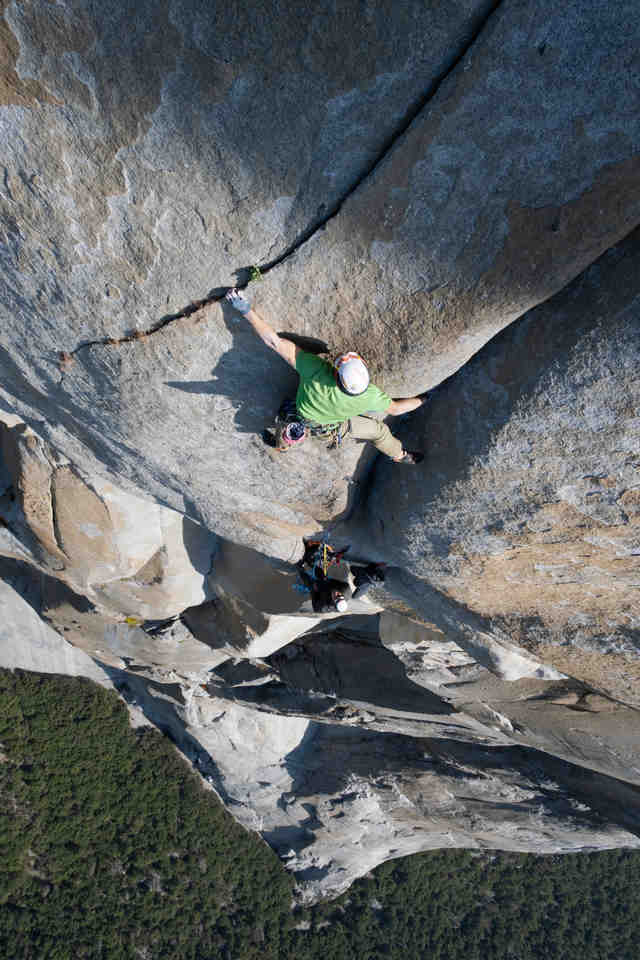

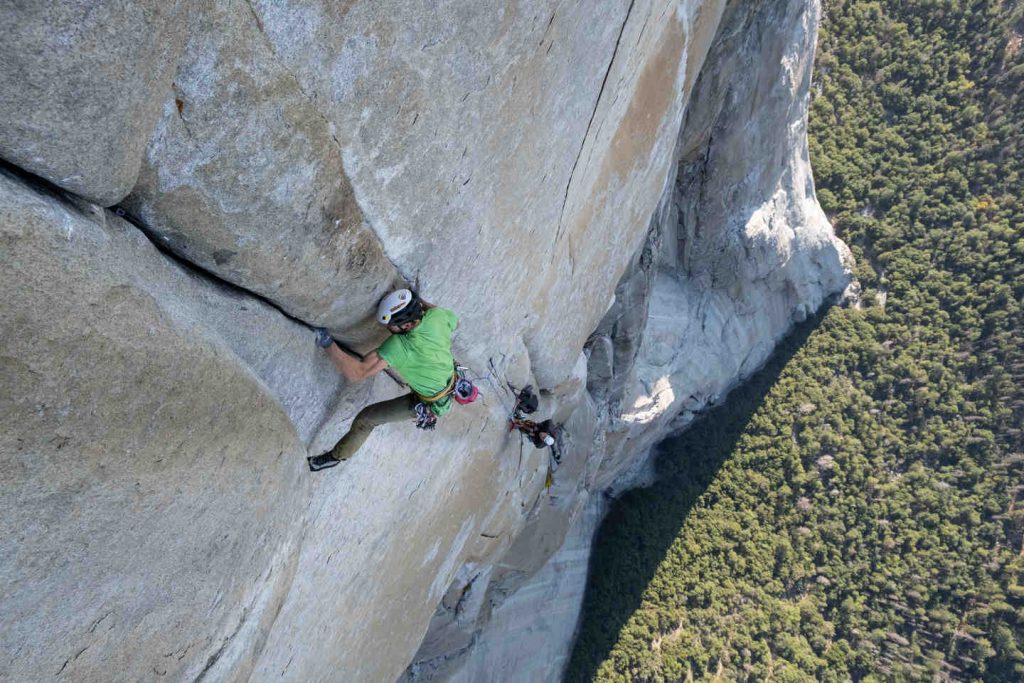

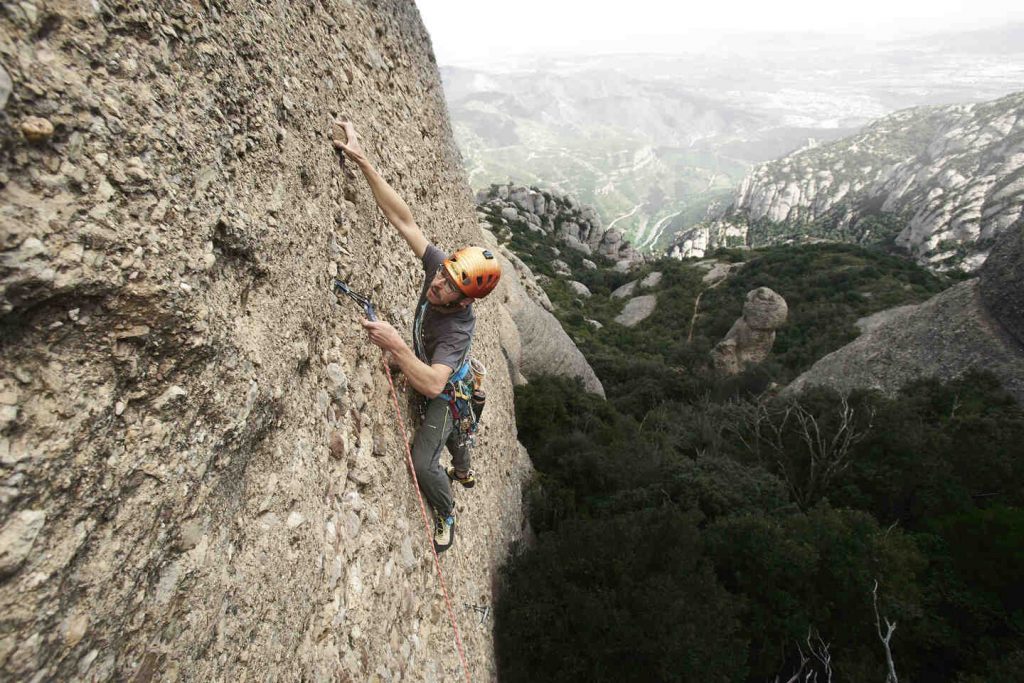

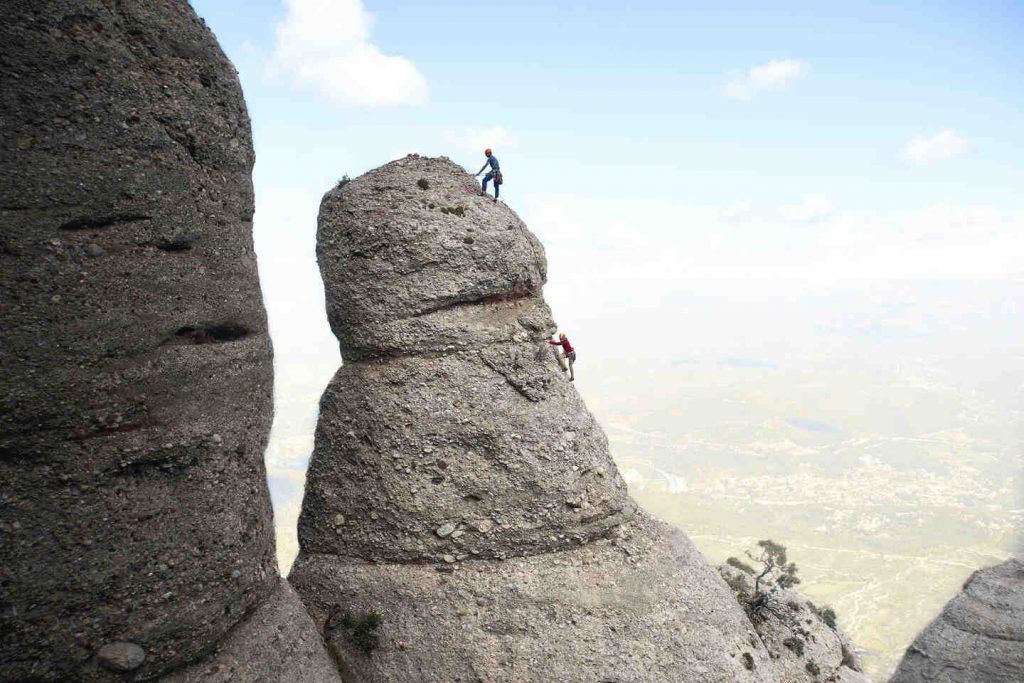

On Sweden’s west coast, it may not offer towering walls or alpine exposure, but what it lacks in height it more than makes up for in sheer granite quality. Scattered across lush green hills, sandy beaches, and quiet farmland, the crags offer some of the finest single-pitch trad climbing in the world — holding their own alongside iconic destinations like Pembroke, Wadi Rum, Indian Creek, Cadarese and Tafraoute.

The granite is a beautiful, rosy pink, smooth yet grippy, with cracks that are both technical and rewarding. While most of the climbing is traditional, it’s not the terrifying kind: gear is generally solid, and many hard routes offer excellent protection, letting you push your limits with confidence. There are more than just pure splitter cracks though. Some routes have flared and intermittent cracks and can demand more thoughtful gear placements and creative climbing — this intricacy gives the climbing extra character and lasting appeal.

Approaches are short and often scenic, with crags emerging from forests or right off the beach. They were so brief, in fact, that I had to go trail running after climbing just to avoid losing mountain fitness. But the upside is clear: with such easy access, you can bring plenty of comforts to the crag — or even stroll back to the van for a hot cup of tea or a cooked lunch. During our visit, the weather was mixed, with rain threatening every other day, so being close to the car gave us the freedom to take chances and climb even when the forecast wasn’t ideal.

The area has a reputation for being bold and serious, but that mostly applies to the top-end grades. For climbers operating at HVS or above, Bohuslän offers the rare opportunity to climb clean, grippy granite in a peaceful, idyllic setting. Part of the adventure is that not every route has bolted anchors — you might end up abseiling from a tree or walking off, and each crag presents something a little different. The guidebooks don’t spoon-feed you every detail, so you need to bring a bit of climbing sense, adapt on the fly, and think for yourself. That’s what makes it feel more like mountaineering than an indoor wall — it’s not commercialized or over-developed. You need the right skills to be safe and self-reliant, and for me, as a British climber, that ethos is all part of the appeal.

I visited in May, and on the days it was dry enough to climb, the temperatures were perfect. But the weather was mixed — a combination of rain and sunshine that made conditions quite variable. I had to think carefully about the aspect of each cliff, how quickly it would dry after rain, how exposed it was to wind, and how the surrounding forest might slow the drying process. I only swam once, as the water hovered around 12 degrees most days — and with the wind, it felt far too cold to enjoy more than a quick dip!

Aside from the climbing, watch out for ticks — I was pulling off about three a day. Many approaches go through long grass, and in Sweden, ticks can carry both Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis, so getting vaccinated beforehand is a good idea.

I recommend doing a bit of research before you arrive. Buying the guidebook or downloading the app in advance will help you identify the best trad climbing routes — there’s plenty of choice, but also a handful of classics you won’t want to miss. Aim for a mix: flash a few routes, but also pick one or two that really inspire you and take the time to work out the moves. Granite can be technical, and if you’re not used to the style, it’s often more rewarding to invest time in a route and climb it well before you leave.

Bohuslän is a perfect training ground for bigger, more committing alpine routes — a place to sharpen your trad skills in a low-stress setting. With its calm, holiday vibe and distinct granite style, it offers a refreshing alternative to bolt-clipping trips in Spain.

A new OAC guidebook, ‘Bohuslan: Selected Rock Climbs’ by Steve Broadbent, is due for publication later this year and will be available from www.oxfordalpineclub.uk so if you are interested in visiting Bohuslanow and know it best trad climbing routes get in touch with Steve to buy a copy of this!

Text by Fay Manners

Pictures by Daniel Coquoz